Like most seasonal tourist communities, Martha’s Vineyard has a small base population of 20,000 that mushrooms to almost four times that size in the summer. While many visitors are rich and famous, the permanent population struggles to maintain a stable living throughout the year. For more than 40 years, John Abrams has been striving to provide these residents with great housing, equipped with state-of-the-art renewable energy technology, through a company called South Mountain. Some years ago, he converted that company into a worker-owned enterprise and then started another firm, Abrams+Angell, to promote the conversion of great legacy companies into worker cooperatives.

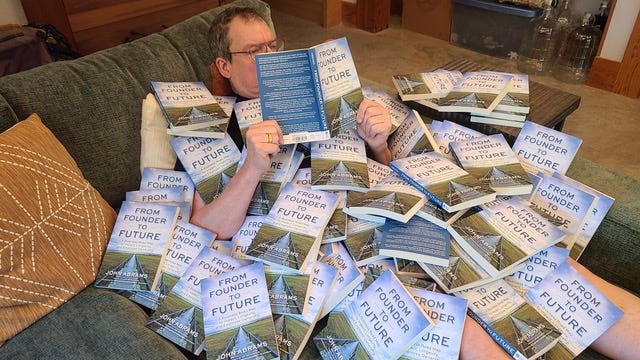

John has a new book out called From Founder to Future, which is as good a textbook as I’ve seen on the rationales and options for worker ownership. John is a gifted writer—on top of his many other skills—and the book is filled with great stories, helpful examples, and many resources. This week, I interviewed John, who shared his history and his hopes for expanded worker ownership models in the future.

If you’re interested in John’s book, he is having a virtual book launch event on June 4 (my birthday!) at 12:30 pm ET. You can register for the event here.

Paying members will also find our latest local investment opportunities below. If you’re not a paying member yet, just click the second button below!

- Michael Shuman, Publisher

A Paid Subscription Gets You:

✔️ News Links

✔️ In-Depth Interviews

✔️ Latest Listings of Local Investment Opportunities

✔️ Monthly In-Person Meetings with Michael Shuman

✔️ Notable New Resources

✔️ Partner News & Voices

✔️ Events

✔️ Job Listings

MS: John, let me begin by expressing my bias: I love your book. And I plan to start assigning it to my business students. Why did you write it?

JA: Thanks for those very kind words, Michael. Business school is one of the places where I’d most like it to be used!

With 3 million U.S. small businesses currently owned by over-55-year-old founders, there will be a massive transfer of wealth in the coming years. This is what we call the Silver Tsunami. Some of these businesses will transition within families, some will be sold to one or two key employees, and others, finding no buyer, will unceremoniously close the doors, leaving gaping holes on Main Street. Many will be scooped up by strategic buyers and private equity pirates. They may get carved up, sold for parts, moved, and abused. Most small business founders want to keep their mission intact, but their advisors—financial planners, succession consultants, attorneys, accountants, and bankers—have no idea about the employee ownership options available, and their substantial benefits. I wrote this book to inspire those owners—and the 32 million employees who helped build those businesses and whose jobs depend on them—to learn about another kind of commerce that makes business a force for good.

MS: As a fellow author, I know that getting a book published is like the birth of a child. How does it feel to see the book in print and ready for release?

JA: When I wrote the book, I had no idea what would be happening at the time of its release. I see the book, in some modest way, as an antidote to the current American spirit—the cruelty, cynicism, and cowardice that seem to have displaced, for the moment, our normal generosity, optimism, and courage. This battle for the soul of our country has occurred throughout our history, but better hearts and minds have always prevailed as we continue the long and arduous journey toward liberty and justice for all.

What may be unprecedented is the degree to which wealth inequality has spiked in recent decades. When it comes to the pursuit of happiness and well-being, working people have been left behind by Democrats and Republicans alike. We can change that. This book is about how businesses can enhance life through cooperation, collaboration, and shared ownership. It is an ode to the America that’s to come, the America where all share its bounty. That’s the message. That’s the story. That’s the hope.

MS: Let’s go back to the beginning—to South Mountain Company in Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, which was your first business. What did the company do, and how did the company get started?

JA: South Mountain happened by chance, entirely by the seat-of-the-pants, in the early 70s. It was a learn-as-you-go experiment. We were a band of hippie carpenters building hand-crafted houses and losing money on every job we did. Hah! Something had to change. I decided to learn about business and figure out how to make subsidized housing for those who needed it, instead of subsidized housing for the wealthy. We made every mistake in the book, but over time, South Mountain became a 40-person integrated architecture, building, and solar company that has been the highest-scoring B Corporation in the world.

MS: That’s impressive. Your first book, Companies We Keep, was about converting South Mountain into a worker-owned firm. What led you to this decision, and what design did you choose?

JA: In 1986, two close friends who had been my employees since South Mountain’s beginning said to me, “We’ve been talking. We don’t want to take the usual route and go off and start our own business. We want to stay here for our careers, but we need more of a stake—more than a wage.” I could have made them partners, but we put our heads together and thought, “If we do our jobs well, this will happen over and over. Maybe we can imagine a structure that would consistently welcome committed employees to ownership.” We did not have to imagine. We luckily stumbled on the concept of the worker cooperative. At the time, there were about a dozen in the U.S. (nearly all of those, by the way, are thriving today 40 years later). The Industrial Cooperatives Association (now known as the ICA Group) was the only organization promoting the idea in the U.S., although there were many worker co-ops worldwide. An attorney at ICA, Peter Pitegoff, taught us about the co-op model and helped us with the conversion and reorganization. On January 1, 1987, I sold the company to myself and several others, and South Mountain became an employee-owned worker cooperative. At the time, there were 12 employees.

It was kinda scary. As the founder and the most deeply invested, I had the most to lose. With distributed ownership, what if this thing that I loved became something that I loved no longer? At times it felt like tugging on the reins of a runaway horse, but momentum carried us, and ultimately it felt like a great hinge point in the company’s young history, a promising path forward to the unknown.

MS: You retired from South Mountain in 2022 and started another firm, Abrams+Angell. What does the new firm do? And do you miss your old firm?

JA: In my new work life, I guide other companies in the transition to becoming worker cooperatives, much like ICA helped us decades earlier. Do I miss South Mountain? I love it with all my heart, but miss it? Hmmm… not really. I used to think I had the best job in the world—to do the work I loved with complete freedom. But my job as the servant leader was to respond to the needs of others, and after half a century of that, I was ready for something new. Today, I get tremendous vicarious pleasure watching the company prosper and flourish under new, solid second-generation leadership.

Having made the ownership change long before, and having developed distributed democratic management and governance over time, we engaged in an intensive multi-year process to build leadership capacity and transfer responsibilities prior to my retirement. This intentional long-term project with the extraordinary South Mountain leadership team and owners was taxing, and there were uncomfortable moments, but ultimately it was entirely thrilling and deeply rewarding.

MS: Your new book, From Founder to Future, provides a really helpful overview of worker ownership options. Which is your favorite and why?

JA: I think all forms of employee ownership are better than no employee ownership at all. I also think that each of the three main forms of employee ownership—Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs), Employee Ownership Trusts, and Worker Cooperatives—can be done well. All have their place; in my book, I tell stories of great examples of each. But my deepest affinity is for the worker cooperative, partly due to my deep familiarity and long experience, but also because workplace democracy and longevity are fully baked into the co-op model. At their best, in my view, other forms of employee ownership borrow from the worker co-op in how they think, act, manage, and govern.

MS: I was struck by your critique of Employee Ownership Trusts (EOTs), which is the model that Patagonia embraced. Yes, the company is now in the hands of a beneficent trustee, but that trustee may not always represent the best interests of the workers. Is this a fixable problem? And what EOT designs are you most excited about?

JA: It all depends on the purpose and goals of those who form the EOT. If the intent is truly to share the wealth that’s created and build a vibrant ownership culture, and the owners take that path in the formation of the trust, the problem you allude to can be entirely avoided. Although the ESOP is the most widespread employee ownership model in the U.S. (there are currently approximately 6,500 ESOPs with 10 million participating employees) and the worker cooperative is the most widespread worldwide, the EOT is gaining significant traction in recent years. It’s relatively new to this country, but the EOT is by far the most common form of employee ownership in the United Kingdom, where it has been developing for roughly 100 years. EOTs excite me the most when their legal purpose is fully committed to the well-being of the employees.

MS: A colleague of mine, who runs a consultancy that primarily employs consultants like me as independent contractors, has been deeply resistant to employee ownership. He has said for years—hey, there’s no value in the company right now, nothing to share, so what’s the point? How would you answer him?

JA: If the company truly has no value, I think he’s absolutely right. But it’s his job as a leader to create that value so that there’s truly something to share. You have to build something that will be worthwhile to the employee-buyers, or any other buyer, for that matter. (Bo Burlingham’s book Finish Big, by the way, is a great treatment of this subject.) Hey look. If you convert a crappy, dysfunctional business to employee ownership you’ll just have a crappy, dysfunctional employee owned company. The beauty of small business is that there’s an opportunity to build something that’s effective, profitable, purposeful, and provides meaningful work. Something valuable, too.

Ownership and leadership are different. Many owners don’t think about either until they are nearly ready to retire. I encourage them to disentangle the two. Ideally, you make the ownership change (which is easier and more transactional) in mid-career, leaving a long runway to the second-generation leadership change (which is more complex and emotional).

MS: I can’t tell from your book whether you’re excited about the involvement of private equity firms like KKR in employee ownership conversions, or terrified. What do you think?

JA: For me, it’s all about the degree to which businesses are being built for long-term stability, and the degree of sharing wealth, ownership, and control with the employees. Some current examples, like Apis & Heritage, which uses private equity funds to create a network of democratic ESOPs with no intention to sell out, are tremendously promising. We will hopefully see more of this in the current era of widespread employee ownership experimentation.

But the KKR model, for all the fanfare and attention it has received, does not diverge from the typical private equity pattern of building companies with the purpose of selling and cashing out in 5-7 years. At that time, the employees may receive a cash windfall—that’s good!—but the employee ownership then disappears, most of the money goes to the investors, and future employees are back in the same place, earning a wage, or possibly eliminated. So to me, the current KKR model is like putting lipstick on a pig. You could call it wealthwashing. Maybe that will change over time; we don’t know yet.

MS: If I can get personal for a minute: Your father, Dr. Herb Abrams, was a hero of mine when I was a law student at Stanford. He used his perch as a world-famous radiologist to raise public alarm about the nuclear arms race. How did his choices influence yours?

JA: My Dad was a fierce advocate for social change, and he influenced me in profound ways. We chose radically different paths, and sometimes that was a source of tension, but we deeply loved and admired each other, and his passion for justice and activism rubbed off on me.

During the last 20 years of his life (he died at 95, and six weeks before his death, he was playing tennis, going to grand medical rounds, and leafleting on University Avenue for Bernie Sanders), we shared extraordinary affection and alignment. He and his father before him truly loved America, and they would have been thoroughly disgusted by the state of our union at this moment in time, which can’t be over too soon. He would have been working hard, as so many are, to resist the current regime and move us to the next iteration of the American story.

MS: Finally, how do you invest locally and elevate your community?

JA: I invest my time and money in solving our local affordable housing crisis. It’s a long-haul, multi-pronged effort to build and repurpose high-performance homes for community residents and essential employees who are shut out of the Vineyard housing market. I’ve been at it for 40 years. Early on, my colleagues and I made the case to our South Mountain clients that the island community can’t be what it is, for them and for us, unless we solve this. They stepped up in amazing ways and committed millions in donations to the cause.

These days, my time is devoted to working with others to convince the Massachusetts legislature to pass a transfer fee bill that would assess a 2% charge on all high-dollar real-estate transactions. We’ll keep pressing legislators until they come through, and my hope is that we will use this steady funding stream to repurpose many of our 18,000 existing buildings from short-term rental properties to stable year-round housing. We can’t build our way out of this crisis without severe environmental consequences; we need to buy our way out of it. I love this work. It changes lives, it makes models for others, and it enhances the community in diverse ways.

MS: Thanks, John, for the important work you do.

JA: Thanks for these great questions, Michael, and I’m grateful for your support! And likewise, I’ve been a long-time admirer of your work as the champion of local economies and community investment.

Read all of our past interviews here.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Main Street Journal to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.